Many people with even quite recent Scottish roots are unfamiliar with the variety of Victorian tenements in Scotland. And in family history research people read and see photos and reports that equate all tenements with slums. Old maps can show street after street of densely packed housing, clustered around heavy industry in the inner city. This high density housing for working people, like the people who lived there and their way of life, were not cared for or valued by wider society, so they went into decline and were, in large areas, swept away.

In our post-industrial age, and once refurbished, most of the so-called surviving “slums” have become desirable properties. Modernised, they can command a premium price over most 20th C. flats in the same area, if they survived in a sympathetic context. “Bought by a wide range of social types, [they] are favoured for their large rooms, high ceilings and original period features”, says Wikipedia. Spot on. But also, the largest or fanciest tended not to become dilapidated or be demolished in the first place.

There’s a wealth of authentic and “poverty porn” images and stories about working class tenements and their slummification and/or ultimate gentrification out there. This is not one of them; but see the notes for links to those and the heart-lifting story of how attitudes were changed and many tenements were saved. Instead, I’m going to introduce one resolutely middle-class 19th century tenement terrace as part of a series of posts based around “our flat”. I’m taking you to Morningside, in Edinburgh.

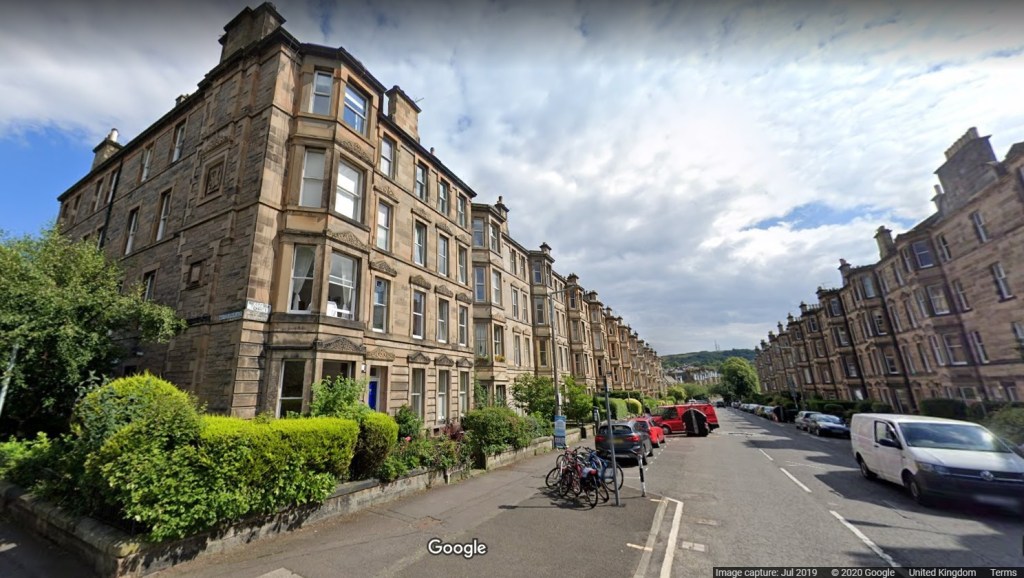

Hullo, Woodburn Terrace.

Other streets in Morningside have grand (and wannabe grand) villas, some have terraced housing, and some a different style of tenement. There are also cottages and modern blocks and oddities. I’ve mentioned the eclectic nature of the area and given some detail on the Victorian (19th C) transformation of the area in an earlier post. And this terrace is another Morningside one-off.

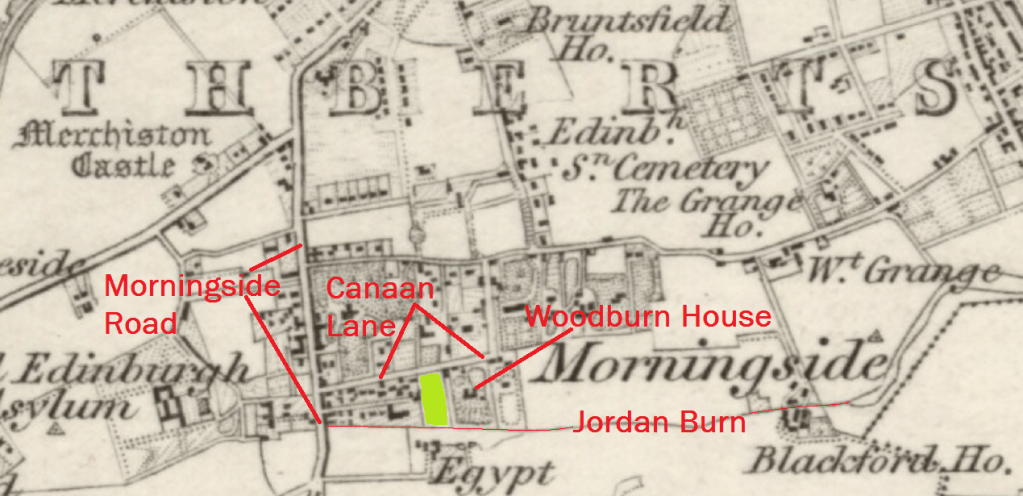

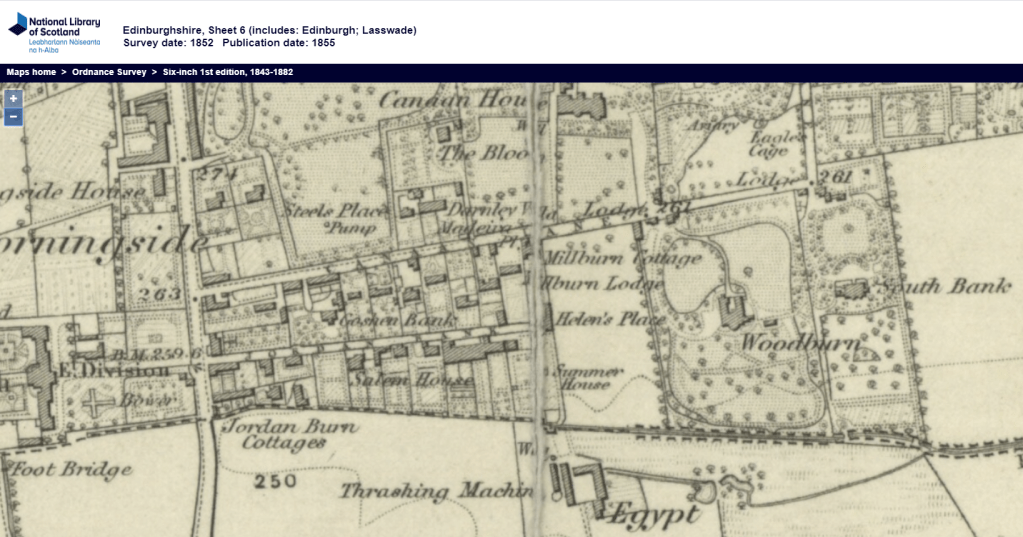

Morningside nowadays is a central suburb south of the Old Town of Edinburgh, a perfect distance to stagger home in the midnight gloaming from August festival shows. 140 years ago, in 1880, the terrace was a “new build”, rearing up on a green field in the Lands of Canaan next to Egypt Farm on the city boundary.

The name of “Littil Egypt” was attested as long ago the days of the plague, in 1585. It referred to the “gypsies” who had been expelled to society’s edges even before that, because in those days this relatively central locale was well out of sight from the old town of Edinburgh: across the burgh loch, then south over a gentle hill covered in ancient woods, down to the burgh boundary.

Morningside remains relatively famous (or infamous) for its stereotyped socially-anxious residents who spend too much of their scant income on trappings of a grand outward appearance (“aw fur coats and nae knickers”). The pretensions attributed to the area’s residents included a local accent. In popular culture it is mocked, even yet. Many will be familiar with Muriel Sparks’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and the central performance by Maggie Smith. The accent was of course not really as it has been caricatured, and in Paul Johnston’s PhD research (published as “Variation in the Standard Scottish English of Morningside” in the journal English World-Wide, in 1984), the simplistic standard myth was blown away: things are (as they always are for academics) complex and fascinating. Sex in Morningside… not really what coal comes in. Even so, inhabitants and others love to discuss their beliefs about the local accent.

Nowadays the area is probably better known thanks to Maisie the Cat and her Grannie. They live in a tenement… I wonder which one? The books and their setting are charming, with a comforting, nostalgic approach. Maisie’s face even decorates the local Number 5 Lothian Bus route.

Woodburn Terrace

Origins

The east side of Woodburn Terrace, perhaps around 1900. There are no large bushes in the gardens, there are gas street lamps, and the iron railings (removed during WW2) are in place. Photo copyright etc unknown, downloaded from facebook.

This street of tenements was planned and built on land purchased (actually, “feued”) by Francis Walkingshaw in 1878. He lived at 6 Jordan Bank very close by (now called Jordan Lane), and was a timber merchant. The previous joint owners had been

- Charles William Anderson, about whom the 1878 and 1881 deeds say he was originally or previously from South Shields in England, “sometime of Cleadon Park”, and located in 1878 at Kirk Hammarton Hall in Yorkshire)

- Mary Anderson or MacGregor (wife of Donald Robert MacGregor, from Edinburgh, a merchant in Leith, and sister of Charles)

They also owned Woodburn House and its grounds, adjacent, described in another post. It’s quite a story as to why they were the owners of the land and why they sold it. There will also be more about that in another post about Mary’s husband.

The Jordan Burn made a natural southern boundary to the land, and also formed the southern boundary of Edinburgh’s municipal domain and parliamentary constituency. This wee burn now flows underground below the south end of the terrace, below a cluster of garages and a Nile Grove house’s garden, which adjoin southern end of the tenements. The burn emerges above ground as it flows east, being open to the air as the southern boundary of the grounds of Woodburn House.

Woodburn Terrace then turns into cherry-tree lined Braid Avenue, shortly thereafter bridging the south suburban railway line before heading up the brae into the lands of Braid. On Braid Avenue the housing has no tenements. It begins with terraced houses, then features semi-detached and detached villas, and provides lovely views to the north.

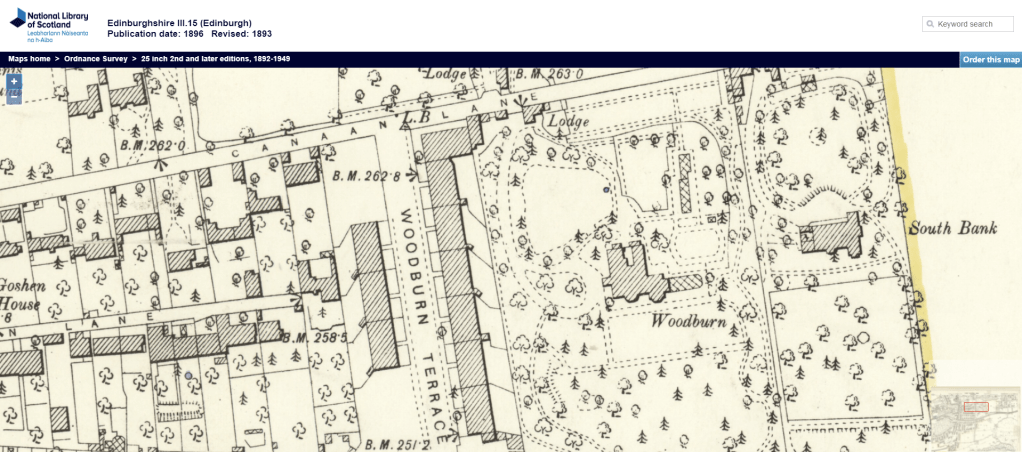

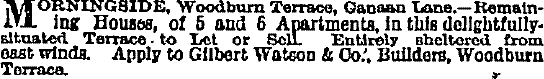

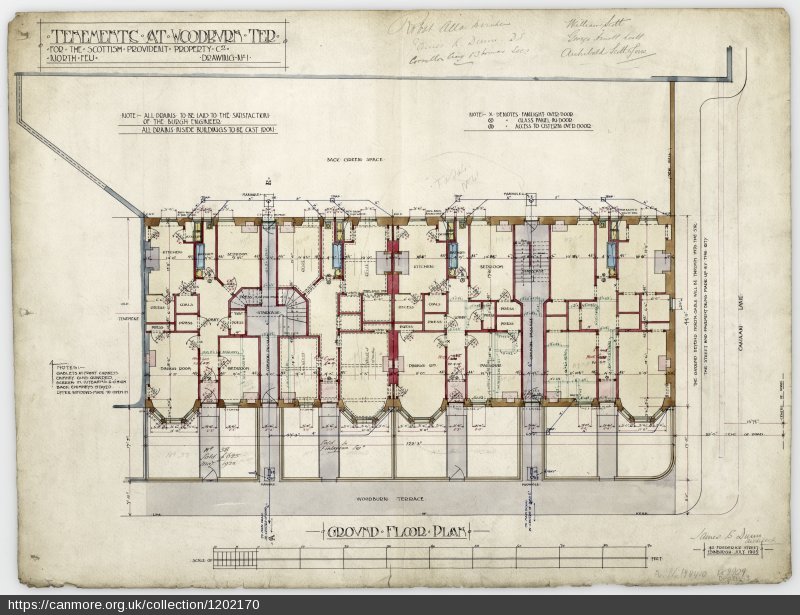

When it was built (from 1880), the terrace ran south from Canaan Lane towards Egypt Farm, the farmhouse of which lay just over the burn, not quite half the way to the bridge over the railway. The terrace was built to a coherent plan, with individual tenement blocks funded by, and built by, different consortia more or less simultaneously, to the architect MacNaughtan’s design. This gave Walkingshaw’s development a pleasing coherent aesthetic.

In June 1878, Walkingshaw committed himself in documents included in our title deeds to build a road and pavements with tenements to the value of £15000 by the end of 1880, which at no more than an average of around £500 would be about 32 flats (four blocks). He was free to choose whether to have shops as part of the design or not: he chose not.

Francis Walkingshaw shall be bound as he hereby binds and obliges himself (First) forthwith to open up a road or carriageway of the breadth of fifty six feet through the lands above disponed as shown and coloured on the foresaid plan and to have the said road or carriageway and side pavements or foot paths permanently made and formed not late than by … [Whitsunday 1880] (Second) to erect substantial dwelling houses with or without shops of stone and lime along the line of the said proposed road or carriageway sufficient to secure to [the Andersons]… due payment of the feu duty and Duplicands therefore aforementioned and in particular to have buildings erected and completed on the said lands to the value of at least seven thousand five hundred pounds at or before the term of Whitsunday Eighteen hundred and eighty and further to have buildings completed and thereafter maintained on the said lands at or before the term of Martinmas Eighteen hundred and eighty [1880] to the value at least of fifteen thousand pounds [£15000] in all (Third) … [Walkingshaw] shall not be entitled to erect any public work or manufactury of any kind within the said lands or any part thereof or to use the buildings to be erected… in any way which may be considered a nuisance…”

Immediately to the west side of the terrace lies Millburn Cottage (42 Canaan Lane), with its remarkably large back lawn, the sheer scale of which in its urban context is surely responsible for its remarkable £1.6m price tag (2019). It was built in 1820, and time has normalised our expectations of luxury: the then-owners must have been furious at a tenement rearing up above their private domain.

Helen’s Place is the other property adjoining the western boundary of the terrace. It was so named on the 1852 OS map, but otherwise was (according to Charles Jones) named Braid Hill Cottage. It looks like a conversion of Millburn’s stables, and is situated on a similarly long thin piece of ground in the morning shadow of the terrace, and is accessed at the end of Jordan Lane (a cul-de-sac).

Edinburgh streets

Edinburgh street naming and numbering are often highly confusing. Streets change their name as they progress, or short stretches of streets sometimes have their own names, even on opposite sides of the road. Even with sat-nav, drivers get confused in Edinburgh. Thankfully, official taxi drivers (like Maisie’s) have “the knowledge”.

Numbers

The main foible with Woodburn Terrace is that, contrary to convention of an odd side and an even side, the numbers run consecutively (north to south) down the east side to the end of the terrace, crossing the road at the (underground) Jordan Burn, just where the street turns into Braid Avenue and the tenements end, rising up to 43 as you go back towards Canaan Lane (south to north).

The normal Scottish approach is rising odd numbers receding on the viewer’s left and even numbers receding on the right (when looking in the direction of higher numbers). Woodburn Terrace is one of the minority that rotates its numbers clockwise.

Names

The street name issue arises too: the single tenement block on the corner of Woodburn Terrace that is oriented mainly sideways, fronting onto Canaan Lane, has its own street name (as well as a partly different design). That bit of Canaan Lane (on the south side only) is called Woodburn Place, and it only comprises numbers 1 (main door) and 2 (flats). The main door flat on the corner of the block that is on both streets is entered from Woodburn Terrace, so is called number 1 Woodburn Terrace. Incidentally, it’s Woodburn Place that hosts the carved stone “1880” that dates the tenements for passers by.

Suffixes

Street name suffixes are something of interest to sociolinguists: the socio-economic connotations of being an “Avenue” rather than a “Road”. There are general patterns in English but also local variation. People’s levels of conscious awareness of any local statistical relationship between suffix, style of road, and typical property values varies.

Some modern local councils have an explicit policy on the use of suffixes. For example, Northamptonshire’s says that “Avenue” should only be for residential streets, “Close” only for a cul-de-sac, “Path” only for a pedestrian road; and they list others that are not acceptable at all. But I bet none are drawn up to reflect socioeconomic factors: that’s subliminal stuff.

When built, it is likely that “Terrace” sounded relatively grand for a street of flats. In his amazingly detailed book on the 19th C. Edinburgh transformation of Edinburgh’s property, Richard Rodgers graphs the average property rental cost in Edinburgh (1890-1914) using data from the valuation rolls. A “Terrace” commanded a relatively high rent.

Our flat

Our block

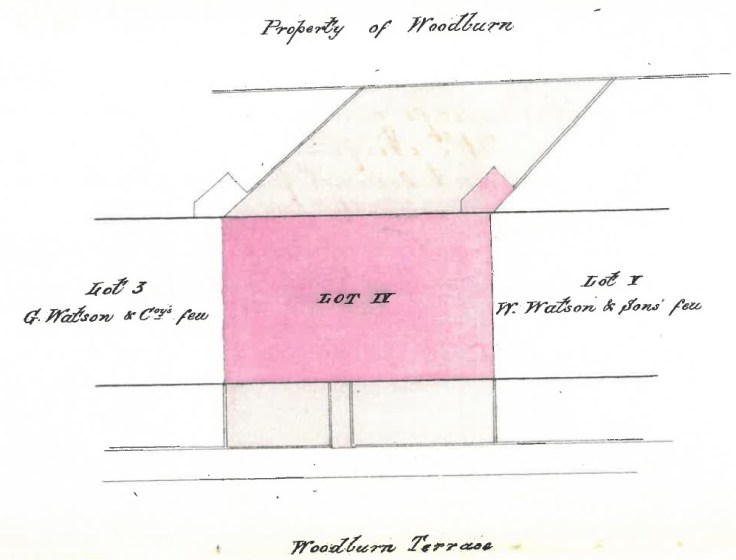

Our flat was in one of six identical blocks in the east terrace, built around 1880. Before it was built, this block was known as Lot IV, and is now numbers 8, 9 and 10. The block was in a prime central location.

The 1881 documentation between Walkingshaw and Wight was witnessed by Knight Watson (and Donald Rae): and Knight Watson is a name that shows up in relation to other properties on the street. He was a lawyer (aged 23), and the younger brother of Gilbert Watson (carpenter and joiner, aged 32), whose company was the developer of Lot 3. At the time of the 1881 census, the building on Lot 4 was listed as vacant, but Lot 3 had been completed, and Gilbert and his brother Knight were in the ground floor flat number 7 Woodburn Terrace with a servant whose name I can’t quite make out.

Interior

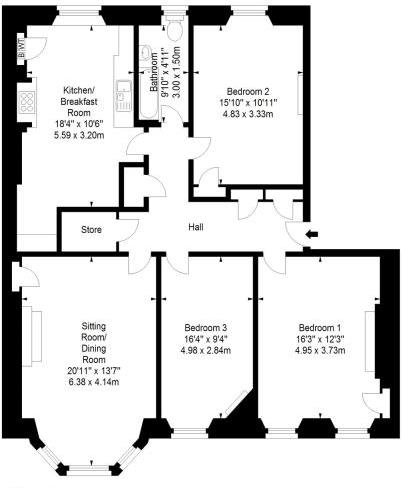

Our own flat was one storey up from ground level, and in the southern “half” of the block. Such flats have a single hall connecting all the rooms, with cupboards. So ours had 11 doors, some of which had glass panels above to filter in natural light from the rooms.

Elsewhere I’ll tell the story of the flat’s first owner, David Wight, who was a plasterer by trade, and responsible for the fancy plasterwork (and other owners and tenants). That post also provide more images of his work on the ceilings of the flat. It’s easy to check out any that are for sale online to get an idea of how the varied interiors look nowadays.

Since the terrace were built, things haven’t changed much, physically, in most flats… apart from decoration… and I would think every bathroom and kitchen. The coal fireplace in each room is usually still present, but blocked and unused. Instead, there’s central heating and radiators, though in some cases rather expensive to run coal-effect open gas fires recreate a cosy period feel.

Not all flats are the same

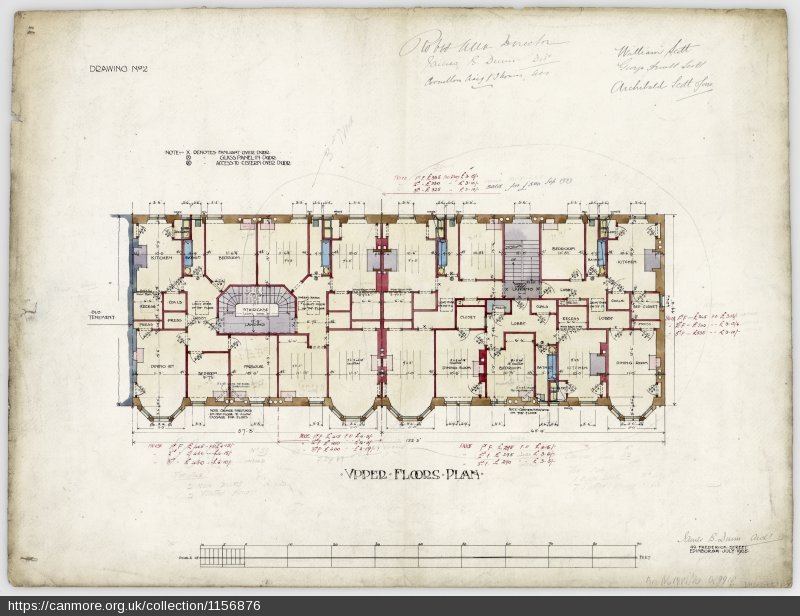

1FL or 9/1 is one of six flats entered from the common stair at number 9: a four storey building is typical of 19th C. Scottish tenements. The six common-stair flats, two per floor, are also often identified nowadays as 9/1 to 9/6 (in the order they are encountered when rising up the stair, on which more below).

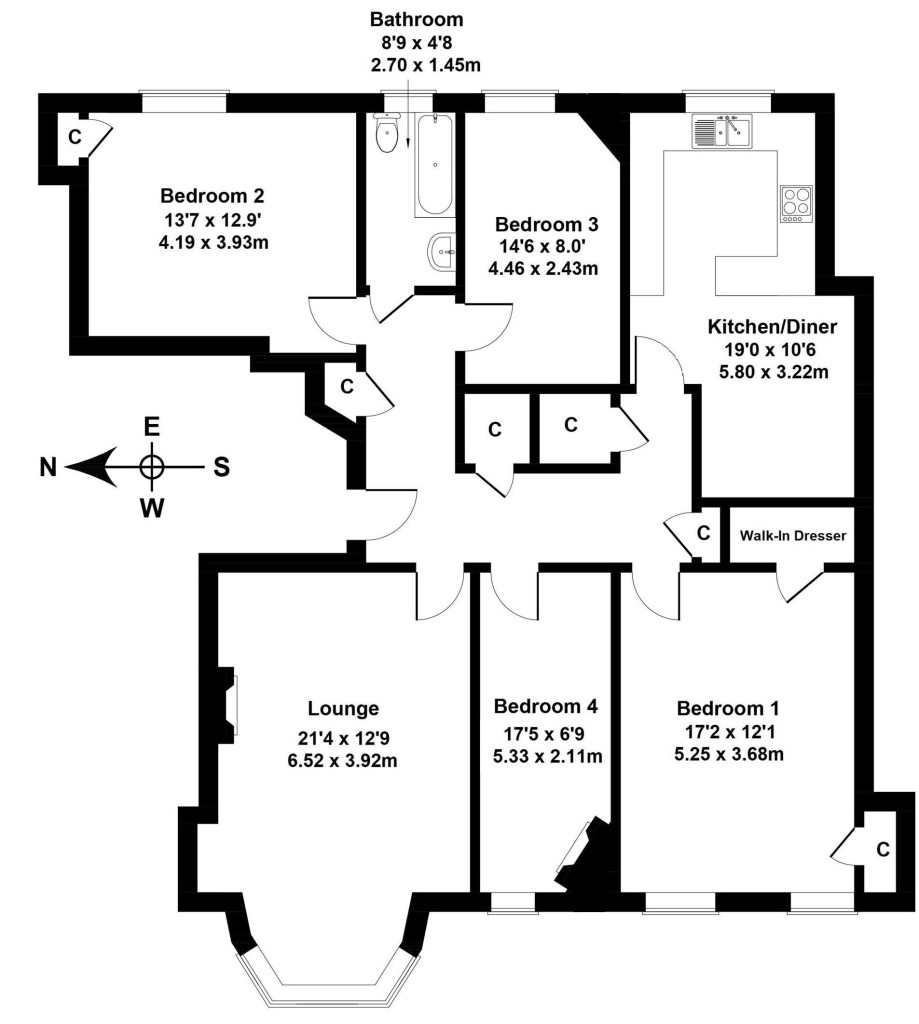

Numbers 8 & 10 are the two “main door” flats on the ground floor in the same block, entered direct from the street through their private front gardens. They also have direct access through their kitchens to the parallelogram-shaped back “drying green” (garden) shared by all eight flats. Number 8 (to the north) is smaller than number 10 (in a similar way as the flats above them) and, and moreover number 10 (and the other comparable flats in the terrace, e.g. numbers 4, 7 & 13) have a kitchenette extension in the back green, visible on the plan as an angled lozenge against the southern common green boundary, and appearing in a photo of the back garden, below. This means each block of 8 flats has 4 different layouts and numbers of rooms, in addition to minor interior differences in the location of large storage cupboards, internal walls and so on.

If Richard Rogers’ findings about up-scale flats in the Comely Bank area of north Edinburgh (page 306) applied in Woodburn Terrace too, then the first floor flats would have been more expensive to rent than the top floors when built, but the most expensive of all were the main door flats (at a 30% premium over the ones in the common stair). Cheaper tenements didn’t differentiate price vertically so much. On a different dimension, price is affected by the size of the flat in terms of area and the number of rooms.

In Macnaughtan’s design, the flats to the south were larger in area and contained one more room (5+ kitchen and bathroom) than their partner on the same landing (4 rooms), as detailed below.

In their basic layout, the 5 apartment flats are all similar. They have an area of about 130 square metres (1400 sqft) including the hall. These 5 apartment flats have their bay-widowed living room near the entrance door, with their kitchen at the opposite end of the flat. The (not mirror-image) 4 apartment flats (around 120 square metres / 1300 sqft) have kitchen and living room both at the far end of the flat relative to their entrance.

Minor details of the number, size and access/location of cupboards, the width of both parts of the hall, and the exact room dimensions: these are the sorts of areas in which the flats within a block differ, and in different blocks (the latter also vary a little in the precise location of the communal stair).

There tends to be an extra small room with no window off the kitchen. It may be a larder entered from the kitchen, or a boxroom/cupboard accessed from the hall and/or the large front-facing room with two windows. In the 4-apartment flats it separates the bay-windowed living room and the rear-facing kitchen, and likewise can be a larder or box-room. They tend to have an internal window above their door. Originally, these may have been a servant’s room. In the 4 apartment flats, they could be entered from the living room, hall, or both. A large coal-storage cupboard sometimes survives in the kitchen, along with a large recess for the original cooking range, not shown on these plans. Every room has a fireplace for a coal fire, occasionally removed and turned into a normal wall.

Oh, and there’s only one toilet. At the moment, when it is fashionable for new-build flats to have an en-suite in every bedroom, this might be a surprise, and seem like an insurmountable drawback. But it’s easy to get by with only one loo: you just need to be polite. Anyway… why anyone would want to waste space in their flat by installing a toilet in their bedroom is completely beyond me.

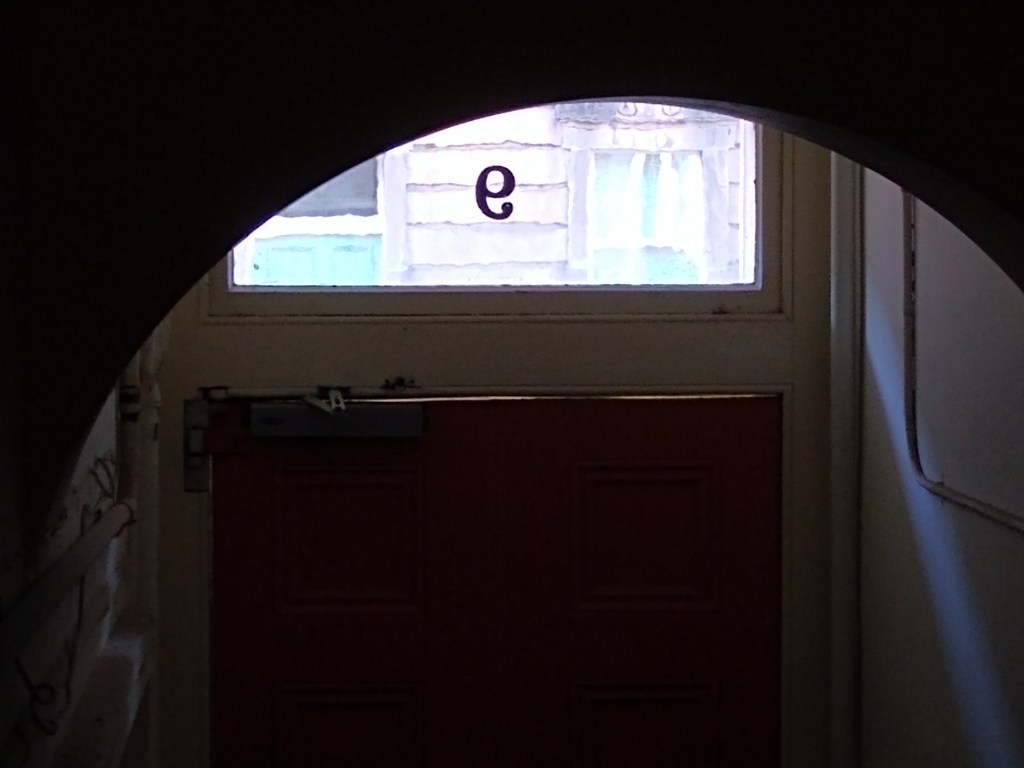

The common stair

Except for many ground floor flats, a tenement flat is entered from a common stair. There is no elevator/lift. The stair usually rises clockwise and may be rectangular, roughly semi-circular, or roughly D-shaped, as here. The stair may have windows or be lit from a sky-light. Our flat was on the first floor (i.e. not at ground level) and was the first door encountered as you ascend. As you arrive on the common landing, it was first door, on the left of the building. Hence, in Edinburgh, this location is often called “Flat 1FL”, (i.e. 1st Floor Left). (It’s on the right as you stand in the street looking towards the block. These are relevant details for genealogists trying to identify which specific flat people used to live in!)

The six common-stair flats, two per floor, are also often identified nowadays as 9/1 to 9/6 (also in the order they are encountered when rising up the stair.) This optional variation causes confusion when some institution or business doesn’t accept there are official alternatives!

Originally, a rope/cable-based system enabled someone in the street to yank a brass knob and ring a bell in each flat, and visitors were admitted by the resident pulling up a lever on the common landing – a tiny minority of these in Edinburgh still function.

I’m from Glasgow, where I knew the common stair as a “close” /klos/ and most didn’t have doors to isolate them from the street. Dialectal variation in the names for lanes, ginnels, vennels, closes, and so on abound, both in their original sense and in relation to tenements.

Numbers 38-43, west side

These were not built by 1896 (as shown in the OS map), and when completed, the two blocks were to a different design, not my MacNaughtan. They are also different to each other (in order to fit the available ground better). The design plans still exist, and are featured on Canmore (curently mis-lablelled, because even reliable sources of information contain errors). Note how these flats are symmetrical within a block.

What about the outdoors?

Front gardens and rear “drying green”

Most main door flats have a private front garden as well as their own front door, as noted above, and they command a premium price relative to their size. The upper flats share the common back green… but it’s a bit of a pain to access it, so some flat-dwellers never use theirs. In most of Woodburn Terrace, the “back passage” is underground, so three flights of stairs need to be used to reach the back garden from even the first floor flats, which is a little off-putting. And its rare for a garden behind a tenement to get a lot of sun, just when you need it. Our garden only got the sun early in the day, so lunchtime outside could be lovely.

Allotments

Vegetable growing was encouraged, and around a hundred years ago, councils set up many allotments on sites not so suitable for housing: narrow strips next to roads or railways, or on steep slopes. The era saw also many lawn bowling greens established in tenement areas. Five or ten minutes walk away are the closest allotments, at Midmar, under Blackford Hill, which in May often looks like this in the evening sun:

Views

The higher the flat, the more light, and bigger views. The higher the better. (Sore knees every time you come home are, I guess, offset by the cardiovascular benefit.) The rear windows of the upper eastern flats look out onto the gardens of Woodburn House. Nowadays these grounds contain many fully mature trees. It’s a view that has clearly matured in the last one and a half centuries, rather than changing fundamentally. Here is the view from our old flat’s kitchen window.

If you lean out a bedroom window over the back green, as I did on a snowy day in February 2020 (the very day we moved out our old flat), the view includes terraced houses that did not exist in 1881, but which were built not long after.

The Woodburn House gardens look beautiful all year round, and act as a virtual extension for the flats that can see them. Number 9 is lucky to look directly towards the villa’s (west-facing) entrance (as shown). Owls, foxes, badgers, woodpeckers, buzzards and bats live, nest and hunt there, and can easily be seen and heard. More rarely, some deer and a lonely rabbits have visited or lived in the grounds. The sky (providing sunrises, views of the moon rising, and with no over-looking neighbours!) is always a pleasure.

Sneaking into the Garden of Eden

Because it’s now a workplace rather than a home, the gardens are permanently accessible, and our children and their friends used to explore, play, build dens, pick wild raspberries, and so on. Outside office hours, natch. As Charles Jones says in his Morningside book (p118): “Beyond the southern slope of the pleasant lawn of Woodburn House venerable trees form a glade though which, in a still charmingly rural setting, flows the Jordan Burn.”

So this is a perfect spot between March and September (sunny and quiet) for gallus Canaan locals to sneakily appropriate some of the parkland (weekends and evenings) for quiet, refined, non-troublesome, Morningsidey “wine picnics”. (And thanks to Morag for that term).

A happy family is a complex mechanism of interlocking parts. It works best when appropriately lubricated. Us slower adults could sit on rugs, enjoying the kids’ gang running around in loops and circles on the lawn. On spritely occasions: rounders. I think we brought some much needed life and happiness to a quiet ghost of a garden.

Going to a park (official or otherwise) means a slightly longer walk home than from a normal back garden, but we were none the worse for that. The fit or brave could use a tree stump to scramble up onto the boundary wall and dreep or jump down. The less gymnastic trauchled home via Woodburn Place. In more recent years they could drop off the empties in one of the terrace’s two communal bottle banks.

A tenement is great, but it does require some effort and compromise, not least in making good use of any available outdoor space.

SOURCES and NOTES

Morningside Heritage Association is on facebook at https://www.facebook.com/morningsideheritage and also on the proper internet at https://www.morningsideheritage.org/ They have a walking Heritage Trail which you can print out at https://www.morningsideheritage.org/about-morningside/#heritage-trail

Smith, Charles J. (1992) Morningside. John Donald Publishers Ltd., Edinburgh. ISBN 0-85976-354-4

Rodger, Richard (2001) The Transformation of Edinburgh: Land Property and Trust in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-60282 – this is a key reference, a weighty academic tome full of detail and original research. I admit I have not benefited from its research, or general themes and conclusions, because I have so far only skimmed and cherry-picked. But it is clearly an essential piece of work and reference for anyone interested in these sorts of topics. Though out of print, 2nd hand copies are available and the table of contents is easy to find (currently here).

Various Title Deeds for 9/1 Woodburn Terrace, unpublished.

Before 1886, Whitsunday was 15th May (fixed in 1599) and Martinmas 11th November, both “Old Scottish Term Days” being a transform from the Julian calendar.

For tenements in Glasgow and how they have been protected, see https://inews.co.uk/inews-lifestyle/travel/glasgow-hyndland-tenements-519152 which focuses on Hyndland in Glasgow, as does https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Housing_in_Glasgow, and for some context on images like the one below see the Springburn Virtual Museum at http://gdl.cdlr.strath.ac.uk/springburn/spring066.htm

Springburn Community Museum 1880-1987

The National Trust for Scotland runs a fabulous Tenement museum in Glasgow.

In Glasgow’s centre, there were waves of change, and many central 19th C tenements replaced an earlier generation: “In 1866, The City Improvement Trust was charged with the task of cleaning up the terrible living conditions that existed in the centre of Glasgow. Learning from their visits to Paris, where they admired the innovative work of Baron Haussmann, the trustees were incredibly successful in adapting the traditional tenement design to rehouse thousands of Glasgow residents.” Edinburgh seems to have retained more examples of the earlier tenements dating from the 1750s-1850s – I lived in a refurbished block in Newington as a student:

If you want to get an idea of what properties are link in a particular area, for family history research, just search. Sales brochures tend to hang around online for some considerable time. As noted above, you can also consult Scotland’s Land Information Service (ScotLIS) and search by map or postcode. Please: it’s taking curiosity too far to actually visit flats for sale! There are plenty tales of people who like to nose about on Thursday evening or Sundays (2pm-4pm) at the traditional open viewings hosted by the seller (or more rarely, an estate agent). Presumably they are the same people who turn up at funerals hoping for an interesting event, or just a sausage roll at the purvey.

Scottish Architects http://www.scottisharchitects.org.uk/architect_full.php?id=100077 lists buildings MacNaughtan was known to have worked on, but Woodburn Terrace is not mentioned (yet). He has left his mark in the local area, being an architect involed with tenenments in Marchmont Crescent, Warrender Park Road, Bruntsfield Place, and Marchmont Road. Perhaps his claim to fame would be the circle bar in the Cafe Royal, of which there are many lovely photographs online.

SCRAN has a useful explantion of feuing, the former usual system of land sale in Scotland (until 2000?), at www.scran.ac.uk/ada/documents/general/feuing.htm

Gordon, J. ed. The New Statistical Account of Scotland / by the ministers of the respective parishes, under the superintendence of a committee of the Society for the Benefit of the Sons and Daughters of the Clergy. Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Vol. 1, Edinburgh: Blackwoods and Sons, 1845, p. 647. University of Edinburgh, University of Glasgow. (1999) The Statistical Accounts of Scotland online service: https://stataccscot.edina.ac.uk:443/link/nsa-vol1-p647-parish-edinburgh-edinburgh

William Moir Bryce, The Burgh Muir of Edinburgh from the Records, The Book of the Old Edinburgh Club (1917-1918), Volume 10. One of many volumes digitised by the Internet Archive, available at The Books of the Old Edinburgh Club. Chapter 11, St. Roque’s Chapel and the Lands of Canaan, pages 167-183. Chapter 12, The Great Plague of 1585, pages 184-188.

Ordnance Survey Name Books Midlothian OS Name Books, 1852-1853 Midlothian, volume 123, OS1/11/123/6 [volume 123 (see the index) has many local place names – Canaan, Egypt, Hebron, Goshen, Jordan]. Woodburn House appears in Volume 15 page 7 – OS1/11/15/7 and Jordan Burn in Vol 15 page 3 OS1/11/15/3 Available from the website Scotland’s Places at https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/ which also provides many other place-linked documentation.

My attempt at listing the owners of Woodburn House is https://noisybrain.wordpress.com/2021/01/17/woodburn-house-canaan-lane/

Edinburgh Council Statutory Addressing Charter doesn’t have a policy for suffixes.

https://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/trauchle – sense 4.

Both Wikipedia and the Gazetteer https://www.scottish-places.info/ are a bit scanty on Morningside, but of course are indispensable.

Peter Stubbs on his site EdinPhoto http://www.edinphoto.org.uk/ has a page which lists at least two other “street history” sites for Edinburgh, and I thought I’d attempt the same here (updating links as necessary) but I met a few difficulties about what to do with: off-line material, online magazine-type short descriptions, dead links and defunct sites, and finally with facebook or other social media pages which are wonderfully inclusive and interactive, but where valuable content is quickly submerged by unedited drivel and where the whole “page” or group can suddenly disappear or alter. Facebook is great for inclusion and has prompted the creation of simplified “websites” in its own little mini-web, but they won’t last. But neither have many of other examples of hard work put online just 10 or 20 years ago. A lot of digital content is gone forever, it seems. So really there’s only one link here, to the exemplary and exhaustive Albany site. I’ll add more if I find any.

- Albany Street – by Barclay Price.

- Arden Street – by Mary Boyle – link broken at original URL and nothing I can see apart from an error message at the internet archive.

I found this very interesting. My Great-Grandmother bought a third floor “new luxury flat” off the plan at 121 Bruntsfield Place. I, with my parents lived in a top flat on Spotiswood Road and a first flat on Arden Street. They all had quite different floor plans. Later in life, I lived in a top flat on Albert Road, Crosshill, Glasgow near Mount Florida and there was a huge difference between the tenements there and the ones in the Gorbals or Govan. There was then, as there is now, variations in purchase price depending on the suburb.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a fabulous track-record of flats. If only they had lifts in them, we could all aim to live on the upper floors forever.

LikeLike

Very very interesting. I loved reading it. I lived in Montpelier Park in the 50’s (pronounced Montpeelyer in my day) and then Albert Terrace which is an interesting street. Must do more research on it. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! We had a brief spin in Montpelier Park too, a top flat.

LikeLike

My mother and grandmother lived in Montpelier Park in the 1940s. Is it no longer pronounced Mont-PEEL-yer? Surely people don’t pronounce it the French way now? (Mong-PELLY-yay)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder… We pronounce it Mont-PELLY-Err, but I don’t know what the range of options is. I have heard an approx French version a few times. Never heard the older version as you both describe it. Cool.

LikeLike

Fascinating. One of my school chums lived in Woodburn Terrace. Main door flat about half way down the west side. I used to be a conveyancing solicitor and was always fasconated by the old title deeds I came across. It was very much a thing that the feuduty apportionment for each flat got lower the higher up the tenement you went.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish I understood some of the legal language better, and knew what to expect from those deeds. Would have saved me some time.

LikeLike

Many are frustatingly uninformative (often due to the absence of plans attached to Register House copies of docs which predate photocopiers) but many contain gems if you know what you’re looking for, such as the apportionment of feuduty between properties revealing insights such as you described. Let me know if you think I could help with any of your future researches. Local history as revealed by old title deeds is a particular fascination of mine – I once spent two days in court giving evidence about it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I came across this by accident. Its so interesting. We lived in a similar flat in Hillside Street from 1977-79. If we had had the money we would have really done it up. For instance the previous owners had panelled over the doors in the 1960s with these plastic handles. It had no central heating. We couldnt afford a proper kitchen but we loved our flat.. One thing I found out was the reason for the presses in the lounge and kitchen. They were to enable the builders to go from flat to flat while they were being built. The doors were later added.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hillside street has a great feel to it. Cheers, glad you wandered by.

LikeLike

That’s really excellent work there! Thank you for sharing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much! I just had another look just now, and there was an awful lot more content that I remember. I ramble on… and thankfully some people find it useful. Cheers!

LikeLike

Excellent Information! Doing research on my Edinburgh ancestors who lived in the Newington ‘hood circa 1880 and they all lived in these tenements. Thanks for helping me understand how they lived.

Keith in Canada

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, this page has been a lot more popular than I could have imagined, and it’s been very nice to know how it helps.

LikeLike

Thank you for a really interesting piece. Something I’ve always wondered, and was trying to work out from those original plans, were these tenements built with bathrooms, or would there have been a communal loo outside? Also, any idea why Edinburgh tenement bathrooms always seem to have a big pane of glass in the door?! That has never made sense to me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

These posher tenements had a bathroom, yes. Other areas of town, and older tenements would have been more similar to others around Scotland. This was definitely a (lower?) middle class street… Clerks, salesmen, engineers etc. Now there are many professional people… A proper economic analysis would be interesting.

LikeLike

And, I have no idea about the translucent glass in bathroom doors… whether it is to let light into the hall from the bathroom… or (because they have small windows) to let light from the hall into the bathroom. For sure, some halls with no windows need borrowed light from fanlights above doors.

LikeLike

AMAZING research, thank you !!…. I wonder if you could help with my own query on modernist architecture in Morningside. I know Ron Cameron (https://www.wowhaus.co.uk/2019/03/26/1960s-modernist-property-edinburgh-scotland/#comment-16044) and was wondering if he built other residential units in the neighborhood.

LikeLike

Gosh, I wish I knew… sadly not!

LikeLike

Great to see this. We lived on Cluny Place and would often play in the hospital woods and the Jordan burn. As its goes im researching book focused around the burn now, and ive already done a comic book with them featured in it, called ‘Once upon a time in Morningside’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds fantastic, is it available? Do advertise it here!

LikeLike

Ah, I see it, and it looks brilliant! https://seanmichaelwilson.weebly.com/morningside.html

LikeLike